Tudor angels of death: the 16th-century obsession with female killers

Men committed most violent crimes in Tudor and Stuart England. But when women murdered, the press had a field day. Blessin Adams asks what drove society’s gleeful fascination with its “angels of death”

"Cruel and barbarous news from Cheapside," thundered the headline on 1676 pamphlet. Read on, it invited, to be horrified by the tale of an "unhuman mistress" who attempted to cook her appearance alive on a spit. Another news piece from 1637, which was entitled “Natures Cruell StepDames: or, Matchlesse Monsters of the Female Sex”, grimly recounted the “unnaturall murthering” of two innocent children by their mothers.

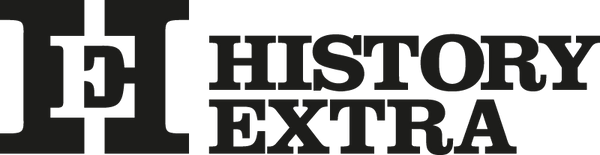

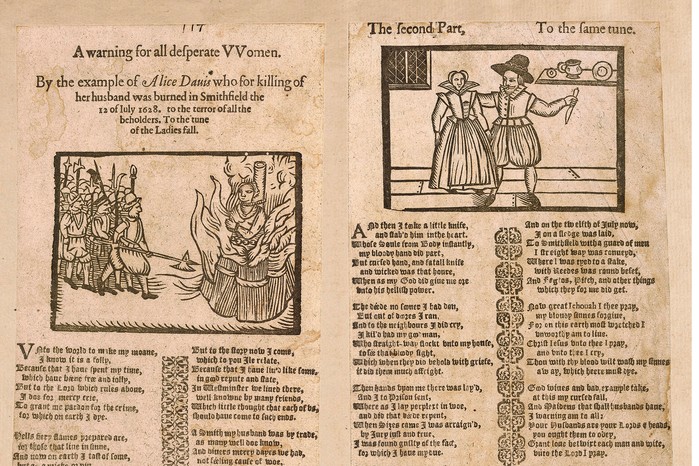

Such gruesome titles might not look so very out of place on today’s newsstands and magazine racks. Like us, people in early modern Britain were fascinated by tales of true crime, murder and violent death. Pamphlets and broadside ballads describing the foul deeds of cold-blooded killers were hugely popular, and were sold on street corners, posted in public houses and even sung aloud to audiences – accompanied by surprisingly jolly tunes.

True crime was big business – and, in the literary marketplace of the 16th and 17th centuries, stories of the most extraordinary and bloody acts sold the greatest number of copies. Such murder pamphlets do not provide a realistic representation of crime in the early modern period. Instead, they reflected their readership’s penchant for the crimes considered the most exciting or the most frightening – and, therefore, the most profitable.

The bestselling and most prolific genre of murder news featured female killers: wives who murdered their unwanted husbands; ‘bastard-bearing’ mothers who killed their babies to escape social disgrace; wicked witches who cast fatal spells on their neighbours. Such cases were vastly overrepresented in the literature, perhaps giving readers a distorted view of the threat posed by women.

- Read more | Lady killers: what 5 murder cases can reveal about the lives of women in the 19th and 20th centuries

At that time, men committed the majority of violent crimes and homicides. From tavern brawls to duels, male violence was ingrained in early modern society – so much so that it was deemed to be normal, even socially acceptable or desirable. Incidents in which that violence overspilled into the crime of murder were held to be deeply shocking but not entirely surprising.

Women, on the other hand, rarely committed violent crimes, and they rarely killed. So when they did, they were considered monstrous and strange, and became objects of intense fascination, believed to pose a genuine threat to society.

Nowhere is this bizarre moral standard more evident than in the reported cases of men and women who teamed up to commit gruesome acts of murder. In these accounts it is almost always the man who lands the killing blow. Yet, as the following case demonstrates – one that involves some shocking acts of violence – it is the woman who is later held accountable.

Inhuman acts

On Christmas Eve 1680, in Ratcliff, London, a seamstress named Leticia Wigington was in a furious temper. Her 13-year-old apprentice girl, Elizabeth Houlton, had transgressed in some small way, either by spoiling her work or by taking a few shillings, and so had to be punished. It was usual in this period for wayward wards to be physically corrected, however what was done to Elizabeth that night was an act of “inhuman barbarity” that went far beyond reasonable chastisement.

Leticia summoned her lodger, John Sadler, and persuaded him to help her punish young Elizabeth. John not only agreed, but he also took charge of what was to follow. For almost an hour John carefully fashioned a whip called “a Cat with nine tails”. This was an instrument designed to tear open the victim’s skin as they were being flogged.

They stripped Elizabeth and tied her up by her wrists with whip-cords. John then proceeded to beat her “for 3 or 4 hours”, while periodically “rubbing the wounds with salt”. Leticia held Elizabeth tightly, and at one point stuffed an apron down her throat to block her “lamentable cries”. Having fainted, Elizabeth was cut down and suffered for three days before dying of her wounds.

Both John and Leticia were guilty of torturing and murdering Elizabeth. However, it was clear that John had taken the leading part in the crime: he had made the murder weapon, he had tied Elizabeth up, and he had administered the deathblows.

The true-crime presses, though, were not especially interested in John. In their reporting of the case he was relegated to the role of an accessory, while Leticia was named as the principal murderer. On one pamphlet claiming to publish Leticia’s confession, her name was emblazoned in large black letters across the front page: “Leticia Wigington of Ratclif... Condemned for whipping her Apprentice Girl to Death.” This was followed by the author’s unwavering conviction that all the evidence against her was “full, clear and undeniable”. In his analysis of the case, the author does not mention John at all.

Another pamphlet reported that “Wigington... was indicted, and arraigned for whipping her apprentice girl to death... She having got one Sadler... to make a whip...” In another publication reporting on John’s trial, it was written that “She [Leticia] got the prisoner [John] to help give her correction.”

In these reports, Leticia was the murderous subject while John was simply a mindless object – no more than an extension of the murder weapon. He was depicted as a background figure who was just following orders. Leticia was the cunning, cruel and calculating murderess who may as well have been wielding the whip in her own hand.

Loud, bold and selfish

Early modern society was strictly hierarchical and patriarchal. Both men and women were held to rigid codes of conduct, and anyone who breached the boundaries of acceptable behaviour was viewed as subversive, even dangerous.

Women of all classes were expected to be subordinate citizens who owed absolute allegiance to the men in their lives: to their fathers, their masters and, especially, their husbands. A woman’s role in society was that of the caregiver and the nurturer: she must be meek, mild and silent. To this end, writers of conduct books instructed women on the virtues of obedience and humility: “A wife must yeeld a chaste, faithfull, matrimoniall subjection to her husband.”

When women killed, they were met with intense public hostility. Such women were seen as being unfeminine

If a woman disobeyed the dictates regarding her gender – if she was loud, bold, selfish, sexually licentious or independent – then she was condemned for failing to play her part in the commonwealth. Such unruly behaviour undermined the very foundations of good society. When women killed, they were met with intense public hostility because they had, seemingly impossibly, transgressed the very laws of man, nature and God. Such women were seen as being unfeminine. Worse than that, they were inhuman.

The true-crime presses were obsessed with such ‘inhuman’ acts, and sometimes went to extraordinary lengths to shift the blame of violent, male-led homicides onto their female accomplices. One such case was reported to have taken place near Romsey in Hampshire in 1686.

William Ives was the landlord of a tavern called the Hatchet, where he lived with his wife, Esther, and their children. Theirs was not a faithful marriage: Esther was having an affair with the local cooper, a “Person of ill Fame” named John Noyse. It was salaciously reported that, in order to “make a freer way for their unlawful Lust”, the adulterous pair conspired to do away with William.

On the night of 5 February, William stayed up late, until about one or two o’clock in the morning, getting blind drunk. At last, he staggered upstairs to bed and fell into a deep sleep. Sensing that their moment had arrived, John and Esther sneaked into his room with the intention to commit murder.

- Read more | Lady swindlers: 6 women who turned to lives of crime and became queens of the underworld

As William lay in a stupor, he was strangled with such force that his neck was broken. A close examination of the body revealed that “much violence appeared to be done to the neck... either by strangling or twisting; insomuch that the blood had issued from him in abundance, and stained the pillow...” William had evidently fought back against his assailant with much vigour, and a great deal of blood was shed. A passing bell-man later testified that he heard a voice shouting “What dost thou do to me, Noyse?”

John and Esther were arrested and later tried at the Lenten Assizes in Winchester on 24 February. In his defence, John blamed Esther, saying that she had provoked a violent quarrel with William, and that he had been obliged to intervene. Yet he did not deny that he was the one who had killed William – in- deed, he could not. Only he had the strength to hold William down, to fight with him, and to apply the necessary force to break his neck. It was also his name that the bell-man heard the victim shouting. John was clearly the murderer, Esther his accessory.

The jury ruled that both John and Esther were equally guilty of the murder, and they were both sentenced to death. Yet when the case was later reported to the public, John and Esther’s roles had been completely reversed. One pamphlet headline dramatically pronounced “A most barbarous and bloody murther, committed by Esther Ives, with the assistance of John Noyse”.

The true-crime presses acknowledged that it was John who had broken William’s neck. However, they held Esther responsible for the killing, because she was the contaminating presence who had, by the very nature of her sex, set into motion this series of murderous events. She was the adulteress who had betrayed her husband; she was the seducer who had besotted the cooper; and she was the instigator who had caused an argument that had resulted in murder. It was she who led John astray and forced his hand; therefore, it was she who was to blame.

Persuasive powers

It was commonly believed that women, from Eve to Lady Macbeth, had the power to seduce and cajole their menfolk, seemingly against their wills, into committing terrible crimes. “Tis said, there is scarce any notori- ous sin,” wrote one contemporary theologian, “but a woman hath a hand in it.” People in the early modern period were particularly enthralled by tales of “lighte and lascivious women” who used their charms to achieve their murderous ends.

Such a case was reported in the year 1583, in the village of Cotheridge near Worcester. There lived an “honest” and “Godly” husbandman named Thomas Beast with his wife, who was simply named as Mrs Beast, and a “hansome Yonge” servant named Christopher Tomson. The familiar story goes that the older and more experienced Mrs Beast (that “harlot” and “wicked woman”) had taken control of the poor, innocent Christopher (that “sweet dallying freend” and “lusty yonker [youngster]”) by the power of her overwhelming sexuality.

Wholly fed up with married life and the constraints a husband put on her blossoming affair, Mrs Beast decided to be rid of Thomas. She convinced Christopher that once Thomas was dead, they would be free to enjoy each other without censure. Christopher was reluctant, but after a great deal of sweet-talk he was eventually persuaded to do the deed.

Having gotten her way, Mrs Beast sharpened a billhook and placed it into Christopher’s hand with the grim commandment “Be sure to hit him right.” Apparently left with no choice but to accept this charge, Christopher set off to find his master working in the fields. It was a cold and quick killing. When Thomas’s back was turned, Christopher struck him “in such cruel manner, [that] there he killed him”. Soon afterwards the illicit lovers were arrested and placed in prison to await trial.

During this time, it was said that Mrs Beast sought Christopher out and plied him with compliments and love-tokens, perhaps hoping he would spare her life by taking full responsibility for the crime. Her actions were noted, and condemned as yet another women’s trick. In the end her flattery did her no good, as she and Christopher were both tried, found guilty and sentenced to death.

It was commonly believed that women had the power to seduce their menfolk into committing terrible crimes

The anonymous author of the true crime pamphlet reporting on these events did their best to enlarge Mrs Beast as a monstrous seductress, and to diminish Christopher as a victim who had been “besotted”, and by the “tirany of loove [sic] possessed” to act against his will. It was a common interpretation that reinforced the popular view that women were indeed dangerous forces of evil: “Oh most horrible and wicked womon, a woman, nay a devill.”

Readers may be struck by how little has changed in the depiction of female killers in our news and true crime media today. When women kill, or are accused of murder, their crimes are almost always highly publicised and sensationalised. The spectres of ‘monstrous mothers’, ‘angels of death’ and ‘black widows’ continue to inspire fear and disgust, and we still refer to female killers as unnatural or as traitors to their sex. In much the same way as our early modern forebears, we expect women to be victims rather than perpetrators of fatal violence.

Yet violence and murder are not the province of men alone, and while women are far less likely to commit acts of blood, it is entirely within their natures to do so.

Blessin Adams is a historian, author and former police investigator. Her new book, Thou Savage Woman: Female Killers in Early Modern Britain (William Collins), is available now.

This article was first published in the April 2025 issue of BBC History Magazine