Liquor, loot and death on the high seas: 5 things you (probably) didn't know about the history of pirates

Sophie Nibbs shines a light on the murky world of the bandits who marauded the high seas in the 17th and 18th centuries

1. Pirates followed strict rules

Despite their fearsome reputations, these maritime bandits often signed up to stringent codes of conduct. Bartholomew Roberts (1682–1722), a well-known and brutal Welsh pirate, enforced rules for his crew, aiming to ensure that things ran smoothly on board. He issued a ban on gambling, which was likely to spark conflict, and lights were to be put out at 8pm. Anyone who wanted to stay awake and continue drinking after that time was required to do so on deck.

The code also dictated that each member of the pirate crew should receive a fair share of the loot. Meanwhile, compensation was paid for injuries, encouraging a sense of loyalty and fairness. The first article of his code states that: “Every man has a vote in affairs of moment; has equal title to the fresh provisions, or strong liquors, at any time seized, and may use them at pleasure, unless a scarcity makes it necessary, for the good of all, to vote a retrenchment.”

Anyone found to have violated the rules could find themselves marooned or even killed. It was often down to the rest of the crew to decide on a fitting punishment for a fellow pirate’s crimes.

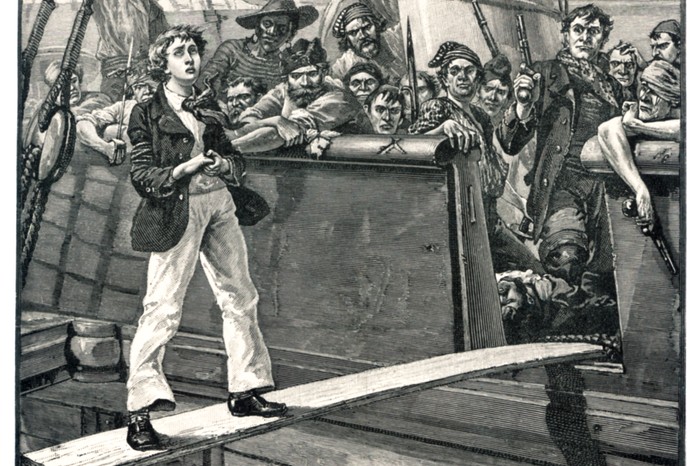

2. They didn’t make captives walk the plank

Pirates dealt with their captives in various practical or brutal ways – killing them outright, enslaving them or marooning them on deserted islands. Sometimes those captured would be spared if they had useful skills or a high ransom value.

In common with many of the dramatic or fantastical ideas we hold about pirates today, the myth of enemies being made to walk the plank seems to have its roots in Captain Johnson’s A General History of the Pyrates (1724), a collection of biographies detailing the lives and dramatic tales of infamous characters. Its mysterious author – thought by some to have been Daniel Defoe but who was more likely newspaper publisher Nathaniel Mist – blended historical accounts with heavily embellished storytelling.

Such myths were picked up by other writers who helped cement them in the public consciousness. Robert Louis Stevenson, for example, wrote of the brutal – albeit mythical – practice in Treasure Island (1883). “His stories were what frightened people worst of all,” recounts narrator Jim Hawkins of the “seaman with the sabre cut” who drank in his father’s inn. “Dreadful stories they were – about hanging, and walking the plank, and storms at sea.”

3. Women were pirates too

There are records of several women who became highly successful pirates, defying societal norms of their time, though some codes contained articles that banned women on pirate ships.

Two of the best-known female buccaneers of the early 18th century, famed for their courage and combat skills, were Anne Bonny and Mary Read. Captain Johnson explained that, in order to be accepted onto the crew of Captain ‘Calico Jack’ Rackham, “they both went through the usual formalities of pirates, and dressed in men’s clothes, for the more concealment of their sex”. When captured in 1720, both claimed they were pregnant and were spared the death penalty. Calico Jack received no such leniency, and was hanged in Jamaica.

Another legendary female pirate was Zheng Yi Sao (c1775–1844), sometimes known as the ‘pirate queen’. Considered one of the most successful pirates of all time, at the height of her power she commanded more than 1,800 ships in the South China Sea. In 1810, she negotiated her surrender with the Chinese government – a very rare way for a pirate’s career to end. She saw out her retirement running a gambling house in Guangzhou (then Canton) until her death at the age of 69.

- Read more | When pirates ruled Asia's waves

4. Not every pirate flag sported a skull and crossbones

Pirate flags, sometimes known as ‘Jolly Rogers’, were intended to strike fear into the hearts of victims, encouraging them to surrender. While the skull and crossbones is the most iconic design, alternatives featured weapons, hourglasses and bleeding hearts – all symbols of danger and death.

If the crew raised a red flag, it indicated that blood would be shed. In a letter from 1724, Captain Richard Hawkins wrote that “[They] hoisted Jolly Roger... in the middle of which is a large skeleton with a dart in one hand, striking a bleeding heart and in the other an hour glass... when they fight under the Jolly Roger, they give quarter, which they do not when they fight under the red or bloody flag.”

- Read more | Did all pirates fly the Jolly Roger?

Another tactic was to sail under the flag of a neutral or friendly nation. Their identity masked, pirates could get close enough to attack a target ship, catching their victims off guard. They sometimes waiting until the last minute before raising the Jolly Roger.

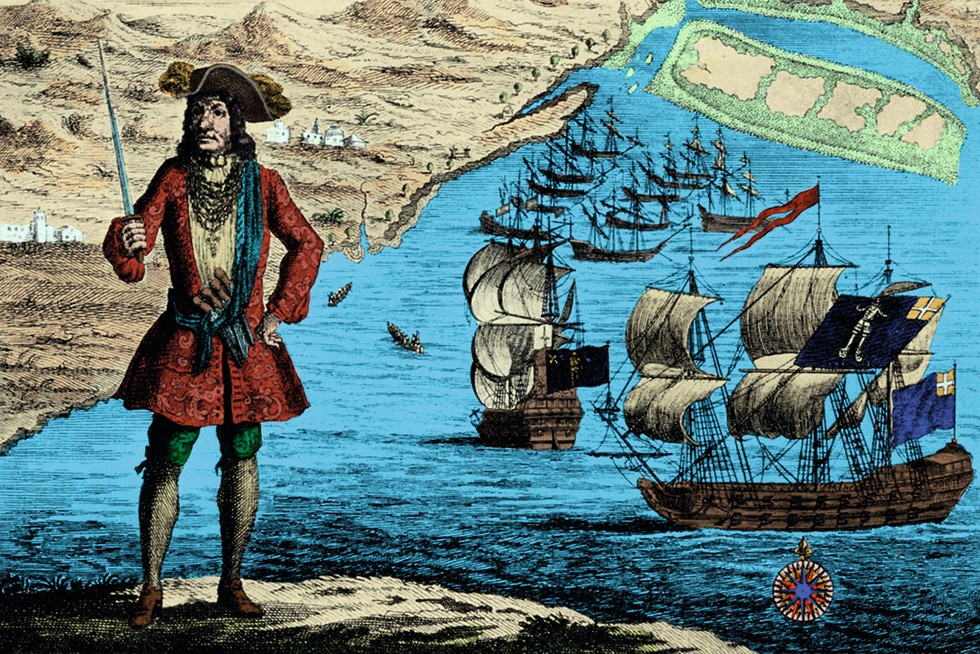

5. Many pirates were former navy sailors

Several pirates served as navy or merchant sailors before being driven to piracy by poor wages, harsh conditions and a lack of opportunities after conflicts ended. Compared with legitimate posts, piracy offered better pay, freedom from oppressive hierarchies and a share of any loot. Unlike on naval vessels, pirate crews were often democratic, electing captains and dividing treasure based on skills and contributions.

Some pirates also came from captured ships. Prisoners, particularly skilled sailors, were sometimes given the option to join the pirates rather than face execution or abandonment. Adopting this recruitment strategy enabled pirate ships to build experienced and loyal crews.

There are also examples of pirates who had formerly been privateers, issued a licence or ‘letter of marque’ by the British government authorising them to attack and capture ships from enemy nations. Some privateers, such as Captain William Kidd, saw opportunities to make vast fortunes, and seized ships they were not permitted to take. As a result, the government in London declared Kidd a pirate; he was captured, found guilty of piracy and hanged at Execution Dock in Wapping in 1701.

Sophie Nibbs is a curator of exhibitions and interpretation, currently at Royal Museums Greenwich.

A new exhibition on the history of pirates opens at the National Maritime Museum, London on 29 March.

This article was first published in the April 2025 issue of BBC History Magazine